Traditional safety models need an upgrade for 2017

It’s time for safety professionals to do some critical thinking on safety models in order to improve their organizational culture. For decades, there have been principles and models that we have used as touchstones for how we approach safety, but how can we build off these for 2017 and beyond?

The Incident Triangle

You can’t think about safety without contemplating the incident triangle, one of the traditional safety models. First introduced by H.W. Heinrich in 1939, the triangle provided a touchstone for the ratio of serious injuries to less serious injuries to events that could have led to an injury (near misses). Thirty years later, in 1969, Frank Bird expanded the triangle to include events beyond injuries and included equipment damage and property damage. Another 21 years passed and the behavioural scientists like Dan Petersen and Aubrey Daniels added another layer to the bottom of the triangle that considered the at-risk behaviours that could lead to incidents with consequences. It has been this version of the triangle that most have used as the touchstone for the past two-and-a-half decades.

In 2017, we need to view this triangle not as a statistically valid equilateral triangle where the ratios are exact but as an assessment of how effective and proactive our organizations are at safety. We need to produce a triangle where the proactive layers (on the bottom) are significantly more robust than the layers that represent the incidents (on the top). Beware of two current detrimental thought streams on the evolution of the triangle. One suggests that as an organization improves in safety, the incident triangle will simply shrink in size but retain the same ratios and same equilateral triangle shape. The downside of this philosophy is that we prematurely believe that our safety is excellent where in fact we have just allowed our view of leading indicators to subside.

The other detrimental thought stream suggests that the triangle needs to have a narrow base and that an organization only needs to look at the leading indicators that could result in a catastrophic event. While this may be helpful for a safety professional to analyze proactive data, it can send a wrong message to workers. They may feel compelled to discern up front which events could be the contributors of “the big one.”

The shape and ratios of the triangle are more than just symbolic of a change — they need to become a touchstone for progression in modern safety. As an organization becomes safer, there will be fewer incidents from which to gather information on the health of the system, so it becomes important to tap into smaller events, near misses and observations of behaviours to gather information that will prevent incidents. A flat incident triangle with a wide robust base is an indication of this progressive safety culture.

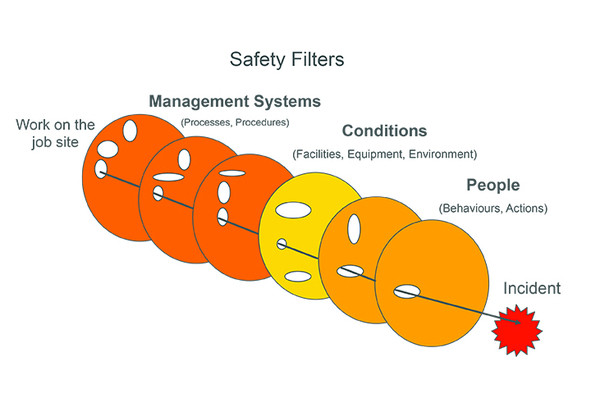

Safety Filters

Several decades ago, Heinrich in 1939 and then Bird in 1970, used a domino model to demonstrate that an incident is the result of an event that triggers another and then another, which eventually results in a loss or injury. The belief was that if we could identify and control the initiating event we could prevent the incident. James Reason advanced this concept in 2000 by using a Swiss cheese model to show that an incident results from multiple failures but it could be prevented if we put more effort into creating barriers, rather than just focusing on the initiating event. The holes in the Swiss cheese represented the path to an incident and the opportunities to prevent incidents lied in identifying and plugging those holes.

In 2017, we need a model that not only demonstrates there are multiple causes, but that the workplace is dynamic and the deficiencies in workplace conditions, management systems and behaviours can combine to result in incidents. We need a model that represents both the multiple failures that cause an incident and the dynamic nature of a system. The rotating safety filters model (see image above) provides a visual that can be used for assessing workplace safety, teaching workers and management how to prevent incidents and assisting with incident investigations.

Inspections and hazard identification are tools that help an organization identify holes in working conditions, equipment and facilities. Audits and assessments help identify holes in the management system filters. Behaviour approaches help identify at-risk behaviours or holes in the people filters in the model. This model promotes a culture of actively seeking out deficiencies before an incident occurs. It can also be used to ensure incident investigation processes are comprehensive and identify all the factors that lead to the incident. An investigation that identifies just a single root cause overlooks the additional holes in the rest of the filters that could also have contributed to the incident. If we don’t identify all the causes, we are doomed to have repeat incidents.